2 Life tables

A life table is an important tool in demography, helping us keep track of birth and death rates of individuals across age or age groups. Life tables are used extensively in human demography, social sciences, and epidemiology, for instance to calculate the remaining life expectancy at each age, and to project future mortality rates. In life history theory, which aims to understand the evolution of different life history strategies, life tables are used to calculate important parameters for ecological and evolutionary dynamics, such as the net reproductive rate \(R_0\) and the long-term population growth rate \(\lambda\).

Life tables are closely connected to age-structured matrix models and life cycle graphs (chapter 3) - these are all different representations of the life history of a given population. While life tables are useful for manual calculations, matrix models are the most efficient way to do life history calculations, and have several additional useful properties. Matric models are also able to describe with many different kinds of structure beyond age structure.

2.1 Learning goals

Define life tables, explain the difference between a dynamic and static life table.

Perform simple life table calculations (e.g. net reproductive rate \(R_0\), generation time \(T_C\)).

Write the Euler-Lotka equation for a given life table and explain how it can be solved to find the long-term growth rate \(\lambda\).

Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of different fitness measures.

Explain how life tables can be used to study the evolution of different life history strategies, including semelparity/iteroparity and clutch size.

2.2 Age-specific survival and fecundity

Before going into the life table methods in detail, this section will introduce the basic concepts of age-specific survival and fecundity, as well as a brief discussion of life history strategies.

One of the most basic ways to describe the life history of a population, is through the age-specific probability of survival and fecundity (average number of offspring produced per individual). The survivorship \(l_x\) is the survival probability from birth (age 0) to age \(x\), where \(l_0=1\) by definition. If we follow a cohort of individuals from their birth until all are dead, and record the number of individuals \(n_x\) still alive in the cohort at each age \(x\), then \(l_x\) is given by \(n_x/n_0\).

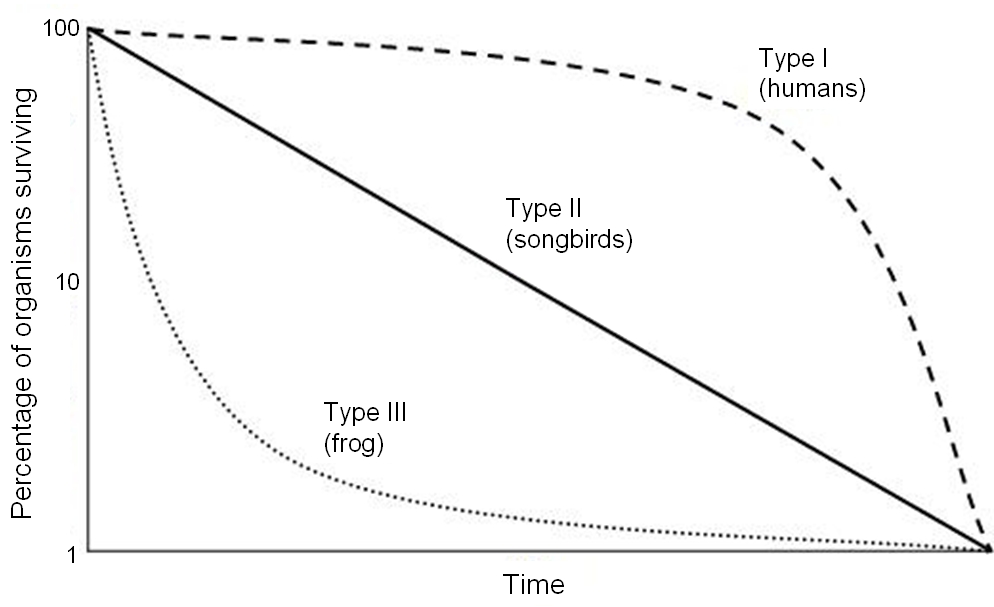

If we plot \(l_x\) against age \(x\), this curve will always (eventually) decline to zero, as no individual can survive forever (although some species are almost immortal). However, the way in which the curve declines contains important information about the life history of the population. It is common to distinguish between three main types of survivorship curves (on log scale, fig 2.1): With type I curves, \(\ln l_x\) declines very slowly for young ages, but rapidly at old age. This kind of survival is typical for many long-lived mammals, including humans and elephants. With type II curves, \(\ln l_x\) declines linearly with age, which means that the mortality is constant and age-independent. This pattern is typical for some birds and smaller mammals. With type III , the \(\ln l_x\) curve declines very rapidly in the beginning (for the youngest ages), and then slowly, which is a typical pattern for many trees (producing seeds that have high mortality rates) and fish.

Figure 2.1: Three main types of survivorship curves (note the log scale on y-axis). Credit: Rayhusthwaite at English Wikipedia / CC-BY (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)

The annual survival probability \(p_x\) is the probability of survival from from age \(x\) to age \(x+1\). The survivorship probability \(l_x\) is related to the annual survival probability \(p_x\) as

\[\begin{align} \begin{split} l_0&=1\\ l_x&=l_{x-1}p_{x-1},\,\:x\geq 1. \end{split} \tag{2.1} \end{align}\]

The fecundity \(m_x\) is the number of newborn offspring produced by an individual at age \(x\), and fecundity curves (plotting \(m_x\) against age \(x\)) can also contain information about the general life history of the species. For instance, in many mammals fecundity reaches a peak and then declines with age, while in many size-structured organisms with continuous growth fecundity increases continually with age. Before maturation \(m_x\) will be zero, so the first age at which \(m_x\) is positive is also the age at maturation (note that in life history we define this age based on observed reproduction, not on physiological traits of maturity).

2.3 Life history strategies and trade-offs

Life history strategies refer to the different combinations of life history traits shown by species or populations, summarized in their age-specific survivorship \(l_x\) and fecundity \(m_x\). The life history is a phenotype, and has a genetic and environmental component. There will always be trade-offs among the life history traits, as individuals have limited access to time and resources, and cannot invest in all traits simultaneously (if they could, evolution would lead to ‘Darwinian demons’ being immortal with infinite amount of offspring). At the species level, life history strategies are the combinations of life history traits that optimize fitness for a given environment. There is more than one solution (strategy) to this ‘’optimization problem’’, which is reflected in the wide range of life histories shown across different species.

Evolutionary changes require the combination of a selection pressure and genetic variation for the traits that are under selection. Demographic methods allow us to quantify selection pressures (through sensitivities, as we will see later) - other methods are needed to quantify the genetic variation of the traits. But before we can define selection pressures, we need a relevant measure of fitness, and we need to understand how fitness depends on the life history (\(l_x\) and \(m_x\)). In the next sections we will go through theory and methods providing this important link, as well as methods to calculate key life history parameters and selection pressures.

2.4 A basic life table

In its most basic form, a life table is a list of age-specific parameters of survival (survivorship \(l_x\), and annual survival probability \(p_x\)) and fecundity (\(m_x\)):

| Age \(x\) | Survival probability \(p_x\) | Survivorship \(l_x\) | Fecundity \(m_x\) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | \(p_0\) | \(l_0=1\) | \(m_0\) |

| 1 | \(p_1\) | \(l_1=p_0\) | \(m_1\) |

| 2 | \(p_2\) | \(l_2=l_1p_1\) | \(m_2\) |

| \(\vdots\) | \(\vdots\) | \(\vdots\) | \(\vdots\) |

| k | \(p_k=0\) | \(l_k=l_{k-1}p_{k-1}\) | \(m_k\) |

No individual lives past the final age, so the annual survival probability in the final age class is \(p_k=0\). However, before they die, individuals in this final class can produce \(m_k\) offspring on their \(k\)’th birthday. The fecundity will also be zero for the first age classes, until the age of maturation (by definition the first age at which offspring are reproduced).

For sexual species, life tables are often defined only for the female subpopulation, under the assumption that survival and reproduction of females are not influenced by the males. If this assumption holds, the male and female subpopulation will grow with the same rate \(\lambda\), and it does not matter which of the subpopulations we use to describe population growth. However, if female reproduction or survival is limited by the number of males, more complex two-sex models are needed to describe the population growth (see e.g. Hal Caswell 2001). We will not consider such models here.

Assuming the life table applies to females only, the fecundity parameter \(m_x\) represents the number of female offspring per female, unless it is specifically mentioned that it includes both male and female offspring. In that case we still need to find the number of female offspring, which is the relevant number for the life table. This depends on the offspring sex ratio. If the offspring sex ratio is 1:1, the number of female offspring is simply the number of offspring divided by 2.

2.4.1 Songbird example

Figure 2.2: A songbird.

As an example, consider a songbird that can live up to 3 years, then reproduces for the last time and dies before reaching age 4. The life table for the female population is given by

| Age x | mx | lx | px | lxmx |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1.000 | 0.2 | 0.000 |

| 1 | 0 | 0.200 | 0.9 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 3 | 0.180 | 0.6 | 0.540 |

| 3 | 6 | 0.108 | 0.0 | 0.648 |

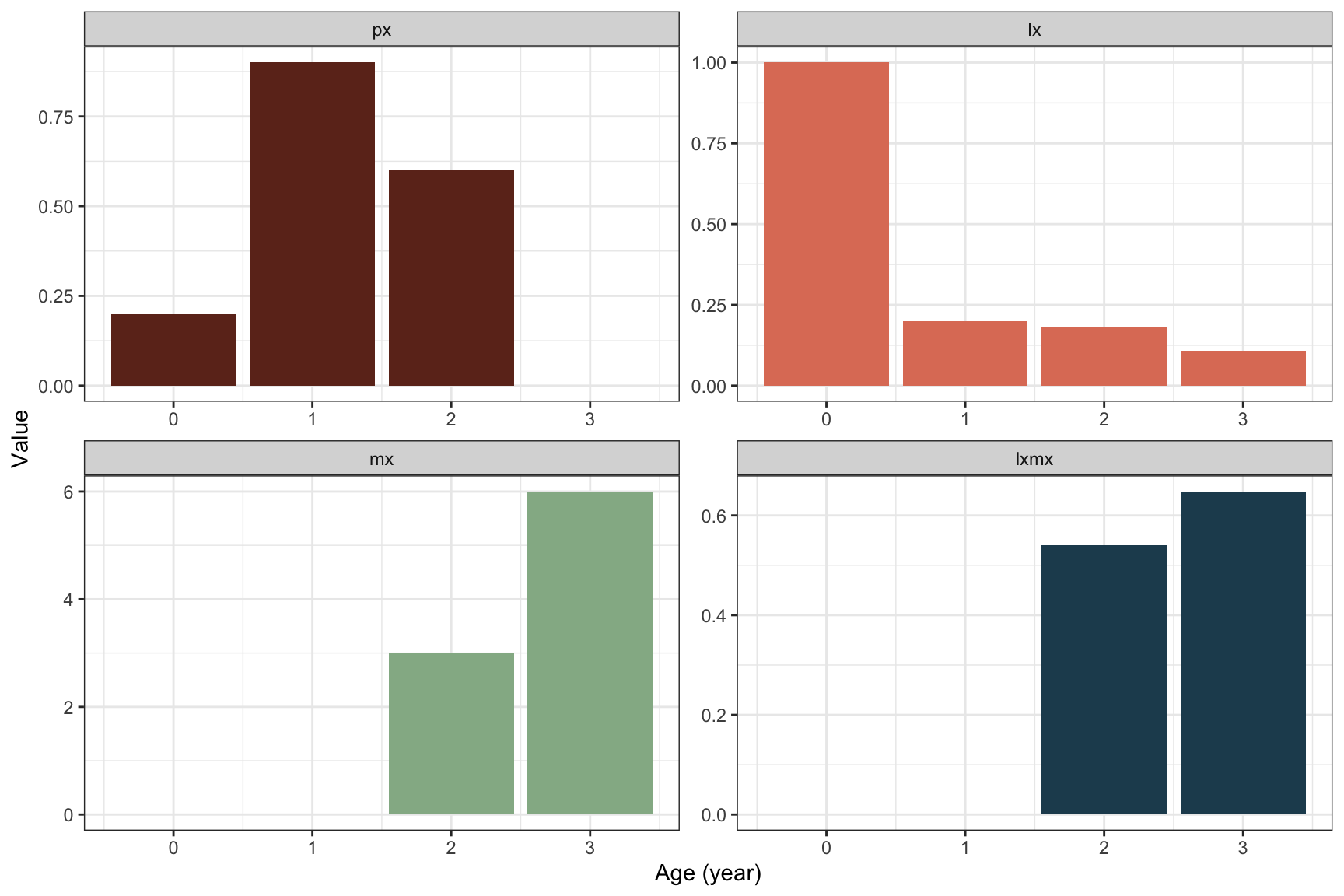

The final column of this life table lists the product of survivorship and fecundity, \(l_xm_x\), and represents the expected number of offspring that an age 0 individual will produce at each age through life. This product occurs in the calculations of \(R_0\), \(T_C\) and \(\lambda\), and it is therefore often useful to include a separate column for it. We will get back to this example throughout this and the next chapter, and some of the R code builds on previous code for this example. Collected parameters and results for this example are provided in appendix B. Copy paste this if you want to run later code chunks for the bird example alone without running all the previous code chunks (you still need to define the relevant R functions).

To produce this life table in R, and plot the columns, we can use the following code:

x <- 0:3 #Age

k <- length(x)

px <- c(.2, .9, .6, 0) #Annual survival probability

lx <- c(1, cumprod(px)[-k]) #survivorship

mx <- c(0, 0, 3, 6) #Fecundity

songbird.lifetable <- data.frame("x" = x, "lx"=lx, "px"=px,

"mx"=mx, "lxmx"=lx*mx)

#For plotting it is useful to use the long format:

songbirds.long <- songbird.lifetable %>%

pivot_longer(c(lx, px, mx,lxmx),

names_to = "VitalRates", values_to = "Value")

songbirds.long$VitalRates <- factor( songbirds.long$VitalRates,

levels=c("px", "lx" , "mx", "lxmx"))

ggplot(songbirds.long) +

geom_col(aes(x=x,y=Value, fill=VitalRates), lwd=1.2)+

facet_wrap(~VitalRates, scales="free")+

scale_fill_manual(values=colors4)+

theme_bw() +

labs( x="Age (year)", y="Value")+

theme(legend.position = "none")

Figure 2.3: Plot of columns from the songbird life table (table 2.1): Age-specific survivorship \(l_x\), annual survival \(p_x\), fecundity \(m_x\), and the product \(l_xm_x\).

2.5 Dynamic and static life tables

There are two main ways of collecting data and estimating the age-specific parameters of survival and reproduction in a population. With a dynamic life table, also known as a cohort life table, an entire cohort of individuals are followed from birth to death, and their survivorship and fecundity is recorded at each age. This approach is often expensive and time-demanding, and in many cases it is not practically possible to obtain such data. The other main approach is the static life table, which is based on recording the survival and reproduction of individuals from the whole population (all age groups) over one or a few time steps. This approach is usually more feasible, and corresponds to taking a cross-section of the population at a given time. However, the approach assumes that we are able to determine the age of individuals, which is difficult in many species. In many studies, more coarse age classifications such as “juvenile” or “adult” are used.

Importantly, the static life table approach is based on the assumptions that 1) the population is stationary (constant or near constant population size over time), and 2) the population has a stable age structure (the proportions of individuals in each age class do not change over time). A dynamic and static life table for a given population will be the same if the age-specific parameters of survival and fecundity are constant over time. For real populations this is rarely the case, but the life tables can still provide a good approximation.

Empirical data in demography

To get reliable empirical estimates of mean survival and fecundity we need long-term individual-based data. Incorporating effects of climate change and other external changes requires even longer time series, as some environmental events occur only rarely but can have large impact on the population.

Study systems providing such detailed long-term data from wild populations are rare, and require much effort to maintain. Those we have are extremely valuable, and much of our ecological and evolutionary knowledge is derived from these study systems.

2.6 Life table calculations

Once we have a life table with columns representing age, survivorship and fecundity, several useful quantities can be calculated. We will focus on three of them: The net reproductive rate \(R_0\), the cohort generation time \(T_C\), and the long-term growth rate \(\lambda\).

All of these quantities can also be calculated directly from a projection matrix, as we will see later (chapter @ref(#s03-MatrixModels)).

2.6.1 Net reproductive rate

The net reproductive rate represents the number of female offspring by which each female will be replaced over her lifetime, on average, and is also known as the lifetime reproductive sucess:

\[\begin{align} R_0=\sum_{x=0}^k l_xm_x. \tag{2.2} \end{align}\]

The product \(l_xm_x\) represents the number of offspring produced at age \(x\) given that the individual survives to that age. Thus, summing up this product for all ages we get the net reproductive rate.

The net reproductive rate is a measure of the population growth rate per generation. For instance, if \(R_0=1.1\) the population will grow by 10% each generation. Thus, \(R_0\) holds information on the population growth rate \(\lambda\), although the two are not the same (\(\lambda\) is per time step, while \(R_0\) is per generation). If \(R_0>1\), we know that the population is growing (\(\lambda>1\)), if \(R_0=1\) then \(\lambda=1\) and the population is stable, and if \(R_0<1\) then \(\lambda<1\), and the population is declining.

Bird example

From the bird life table (table 2.1), we see that the age at first reproduction is 2, and that although few individuals live to age 3, this is the age class of highest expected number of offspring. The net reproductive rate is in this case

\[ R_0=\sum_{x=0}^3 l_xm_x=0+0+0.54+0.648=1.188. \] Thus, each female is expected to be replaced by 1.188 female offspring on average. From this number we now know that the population is growing (\(\lambda>1\) since \(R_0>1\)), although we do not yet know the value of the population growth rate \(\lambda\).

In R, we can find this from the life table (or the vectors) as follows:

R0.lifetable <- function(lx, mx){

sum(lx*mx)

}

#Bird example:

R0_Bird <- R0.lifetable(lx, mx)

R0_Bird## [1] 1.188Note that R automatically multiplies each element of the vectors first, before summing the products.

2.6.2 Cohort generation time

The generation time reflects the ‘pace of life’ of a species. Many biological properties (physiological rates, other life history parameters) scale with generation time. For age structured populations with overlapping generations there are different ways to define generation time. We will use the socalled cohort generation time, which is the mean age at reproduction of all the \(R_0\) offspring the average individual produces:

\[\begin{align} T_C=\frac{1}{R_0}\sum_{x=0}^{k} xl_xm_x. \tag{2.3} \end{align}\]

The expression \(xl_xm_x/R_0\) represents the fraction of the mean lifetime reproduction (\(R_0\)) that happens at age \(x\). By summing this up for all ages (and moving 1/\(R_0\) outside the sum) we get the average age at which reproduction occurs.

Bird example

Using the measure defined above and the values in table 2.1, the cohort generation time for the songbird is given by

\[ T_C=\frac{1}{R_0}\sum_{x=0}^k xl_xm_x=\frac{1}{1.188} (0+0+2\cdot0.54+3\cdot0.648)=2.54. \]

In R, we can find this as follows:

TC.lifetable <- function(x, lx, mx){

R0 <- R0.lifetable(lx=lx, mx=mx)

sum(x*lx*mx)/R0_Bird

}

#Bird example:

TC_Bird <- TC.lifetable(x, lx, mx)

TC_Bird## [1] 2.5454552.6.3 Approximation of long-term growth rate

Since \(R_0\) is an estimate of the per generation growth rate and \(T_C\) an estimate of generation time, we can use them to estimate the population growth rate per time step, the intrinsic growth rate \(r\) (see chapter 1 on exponential growth):

\[\begin{align} \ln\lambda = r \approx \frac{\ln R_0}{T_C}. \tag{2.4} \end{align}\]

This approximation assumes that all offspring produced during the lifetime on average (\(R_0\)) are produced exactly at age \(T_C\), rather than at different ages. It can be a good starting point for the more accurate calculation of \(\lambda\) based on the Euler-Lotka equation, which is the topic of the next section.

Bird example

Using the values calculated above, we get the following approximation of \(\lambda\) for the songbird:

The estimate of \(\lambda\) based on \(R_0\) and \(T_C\) is given by \[ \lambda\approx e^{\ln R_0/T_C}=e^{\ln 1.188/2.54}\approx 1.07. \]

In R, we can find this as follows, using the bird example:

exp(log(R0_Bird)/TC_Bird)## [1] 1.0700212.6.4 Euler-lotka equation

The Euler-Lotka equation is an essential equation in life history theory, because it provides the link between the life history of the focal population, as described by the age-specific fecundity \(m_x\) and survivorship \(l_x\), and the mean fitness \(\lambda\) (long-term population growth rate), associated with that life history.

To derive the Euler-Lotka equation, we first define the number of newborn individuals at time \(t\), which is the sum of the newborns produced at each age:

\[\begin{align} n_0(t)=\sum_{x=0}^{k}n_0(t-x)l_xm_x. \tag{2.5} \end{align}\]

Here, \(n_0(t-x)\) is the number of newborn \(x\) years ago (that are now aged \(x\) years). This number is multiplied by \(l(x)\) to obtain the number of them that are still alive at age \(x\), and then by \(m(x)\) to get the total number of offspring they produce at age \(x\). The sum is over all ages, to get the total number of offspring (left side of the equation). For the next step of the derivation, we first assume that the population, and therefore each age class, grows steadily and exponentially at rate \(\lambda\). Because the population grows exponentially, we assume that the number of newborn over time will follow an equation on the form \(n_0(t)=Q\lambda^t\) (remember the equation for exponential growth), where \(Q\) is an unknown constant. Inserting this for \(n_0(t)\) and \(n_0(t-x)\) in the equation above, we now get

\[\begin{align} Q\lambda^{t}=\sum_{x=0}^{k}Q\lambda^{t-x}l_xm_x. \tag{2.6} \end{align}\]

Finally, we divide each side by \(Q\lambda^t\) to get the Euler-Lotka equation (remember that we can write \(\lambda^{t-x}=\lambda^{t}\lambda^{-x}\)):

\[\begin{align} 1=\sum_{x=0}^{k}\lambda^{-x}l_xm_x. \tag{2.7} \end{align}\]

It is now tempting to try to rearrange this equation to isolate \(\lambda\) on one side, to get a ‘nice’ expression for \(\lambda\) as a function of the cumulative survival and fecundity. Unfortunately, this is not possible (except for a few special cases)! This equation can only be solved numerically, for instance by trial and error (change the value of \(\lambda\) in the expression until you find the one that leads to the sum being close to 1).

Bird example

The exact value of \(\lambda\) is defined by the Euler-Lotka equation, which for the bird example (table2.1) is given by

\[ 1=\sum_{x=0}^{k}\lambda^{-x}l_xm_x=0.54\lambda^{-2}+0.648\lambda^{-3}. \] We can solve this by trial and error, and a good starting value for \(\lambda\) is the estimate from \(R_0\) and \(T_C\), \(\lambda \approx1.07\). However, solving the equation is more easily done in R.

One of several possible approaches is to use the function uniroot(). You are not expected to memorize the details of this approach, but it is shown here as it can be useful with lifetables. Uniroot searches for the solution of a function (i.e. the value of its first argument that makes the expression in the function equal to zero) within a predefined range. For this to work for the Euler-Lotka equation, we need to rearrange it to get an expression that equals zero (just move the number 1 from right-hand side to left hand side), make sure \(\lambda\) is the first argument of this function, and then apply the uniroot function:

#Rearranging Euler-Lotka function:

EulerLotka <- function(lambda, x, lx, mx){

sum(lambda^(-x)*lx*mx)-1

}

#Apply uniroot to find lambda, store the result

lambdabird <- uniroot(EulerLotka, x=x,

lx=lx, mx=mx, interval=c(.1,2))$rootWith this approach the estimated value is \(\lambda=\) 1.07025, close to the approximated value calculated above.

You have now seen an example of how the Euler-Lotka equation can be solved in R, but this approach is not commonly used. It is much more convenient to find \(\lambda\) based on the projection matrix from a matrix model, which is the topic of section 3.

2.7 Fitness measures in life history theory

In the context of life history theory, fitness is often measured by the long-term growth rate \(\lambda\) (or equivalently \(r=\ln\lambda\)) as defined by the Euler-Lotka equation, or by the dominant eigenvalue of the projection matrix (chapter 3).

Another fitness measure which is commonly used, is the lifetime reproductive success, \(R_0\) (equation (2.2)). This measure does however not account for timing of life history events (at which ages reproduction happens, for instance), and thus ignores an important aspect of the life history. Both \(\lambda\) and \(R_0\) are based on the assumption of constant age-specific survival and fecundity in the life table, and neither is a good measure of fitness in the case of strong density- or frequency-dependence (because \(\lambda\) and \(R_0\) are both based on average values that are not useful for understanding selection in such situations). Life history theory deals mostly with outcomes of evolutionary processes in the long run (i.e. evolution of entire life histories) and to a less extent the short-term dynamics of gene frequencies (population genetics). With strong density or frequency dependence, and where the purpose is to estimate gene frequencies over time, other methods are better suited (e.g. adaptive dynamics frameworks). These are not considered here, but note that the measure of fitness will also generally be different in these cases.

Following the convention through most of the literature on life history evolution and quantitative genetics based on demographic models, \(\lambda\) is the main fitness measure for a structured population in a constant environments.

2.8 Semelparity and iteroparity

Some species, including most mammals, have multiple reproductive events during their lifetime. This is known as iteroparity, while semelparity applies to species that reproduce only once. This mode of reproduction is used by annual plants as well as some perennials, several invertebrates, many fish species, and a few mammals. In salmon, some species are iteroparous and others are semelparous. From a life history perspective it is interesting to know under which circumstances evolution of iteroparity versus semelparity is favored, and we can use the knowledge from life table methods to investigate this question.

Cole (1954) was among the authors who were interested in this and other life history questions. He is known for Cole’s paradox, which was only a small part of a larger article. In this example, Cole compared two species: The first is semelparous and lives for only a year, after which it produces \(m_1\) offspring and dies. The second is iteroparous and lives forever (survival probability of 1 each year), producing \(m_2\) offspring each year. Now look at the annual growth rate (fitness) \(\lambda\) for each species: Species 1 gets \(\lambda_1=m_1\) (since each individual leaves behind \(m_1\) individuals on average each year), while the second species gets \(\lambda_2=1+m_2\) (each individual leaves behind \(1+m_2\) individuals each year, i.e. itself plus offspring). What would it take for the semelparous species to have higher fitness than the iteroparous one?

\[\begin{align} \lambda_1 > \lambda_2\\ m_ 1> 1+m_2. \end{align}\]

In other words, as long as the semelparous species (species 1) produces at least 1 more offspring per clutch than the iteroparous one (species 2), it would have the same or higher fitness. This is known as Cole’s paradox, as it seems unlikely that an immortal species should get the same fitness as a mortal one having just one more offspring per clutch. It is also a paradox that semelparity is not more common (in birds an mammals) if semelparity is so ‘cheap’ to evolve. The clue to ‘resolve’ the paradox is that the assumptions for each species are too simplistic to apply to the real world. Once we take more realism into account, for instance drop immortality but instead have an annual survival probability \(p<1\) for the iteroparous species, and introduce a difference between adults and juveniles (where juveniles cannot reproduce), iteroparity becomes relatively more favorable and it would cost more to switch to a semelparous life history.

Note that while semelparity is ‘rare’ in birds and mammals, which likely motivated the need to explain how it evolved (compared to iteroparity), it is common in other taxa.

2.9 The Lack clutch

The concept of the Lack clutch originates from ornithology, but applies generally to other organisms as well. It is named after the ornithologist David Lack, who suggested a pioneering baseline model for understanding life history trade-offs that affect clutch size (Lack 1947).

The problem started from the observation, including brood manipulation studies, that many birds seem to lay fewer eggs per clutch than they could manage to raise to fledging (independence). This suggests there could be one or more life history trade-offs constraining birds from laying larger clutches, and that the observed clutch size perhaps represents some fitness optimum for the current environment. Lack’s model assumes that this trade-off is with fledgling survival, and he also assumed this trade off was linear. In that case, the optimum clutch size, from the parent’s point of view, is the one that maximizes the number of offspring that survive to fledging. This clutch size is known as the Lack clutch. Each offspring, on the other hand, would prefer (from a fitness perspective) to have all parental effort to itself, so that the optimum clutch size from the offspring point of view is 1. This is an example of a parent-offspring conflict (where offspring and parents do not ‘agree’, evolutionarily speaking, on what is the optimum parental investment in a clutch).

We can describe the Lack clutch model mathematically as follows. Let \(N_e\) be the number of eggs laid in a clutch, and let \(l_f(N_e)\) be the probability of survival from egg laying until fledging (when offspring are independent). It is a linear function of the number of eggs in the clutch:

\[\begin{align} l_f(N_e)=1-cN_e, \end{align}\] where \(c\) is the slope of the relationship. The number of survived fledglings is then given by

\[\begin{align} N_f(N_e)&=l_f(N_e)N_e\\ &=(1-cN_e)N_e\\ &=N_e-cN_e^2. \end{align}\]

This is a quadratic function, and we find the maximum (or minimum) where the derivative is equal to zero. The corresponding value of \(N_e\) is the Lack clutch \(N_e^*\):

\[\begin{align} \frac{dN_f(N_e)}{dN_e}&=1-2cN_e\\ 1-2cN_e^*&=0\\ N_e^*=\frac{1}{2c}. \end{align}\]

This tells us that the stronger the trade-off with offspring survival (size of the slope \(c\)), the lower the Lack clutch size. The Lack clutch is larger than one only for \(c<0.5\).

The Lack clutch is based on a simple model, with some important assumptions that do not necessarily hold for real world examples. The model considers only one (but important) trade-off: Clutch size versus offspring survival until fledging. However, other trade-offs could also affect the clutch size, such as parental survival and future reproduction. Another important assumption is that the trade-off between offspring survival and clutch size is linear, but this is just a convenient assumption. In many cases the offspring survival could be a non-linear function of clutch size (for instance if parasitism affects large clutches more than small ones). Furthermore, the model assumes a constant environment, and that parents treat all offspring of the clutch equally. In many species, for instance in many raptors, parents favor the largest / oldest of the siblings, so that younger siblings only survive in very good conditions (or if the older ones die for some reason). In these cases, the younger offspring may represent an “insurance” for the parents, and effects like this are not captured in the simple Lack clutch model. Still, this is a good baseline model for exploration of more complex hypotheses around the evolution of clutch size.

2.10 Exercises

For suggested solutions, see appendix A.

Exercise 2.1

The table shows the average lifetime number of children per woman in some different countries.

| Country | Children per woman |

|---|---|

| Mali | 5.8 |

| Tunisia | 2.2 |

| Australia | 1.7 |

| Norway | 1.6 |

| South Korea | 0.9 |

Assume exponential growth, and use the approximation in equation (2.4) to answer the questions:

What is the annual population growth rate (\(\lambda\)) of each country, given different assumptions for the value of generation time?

How many years does each country need to double in population size, if we assume a generation time of 25 years?

How well / poorly do you think these populations meet the assumptions made for these calculations?

Exercise 2.2

Figure 2.4: Flowering plant

A botanist follows a cohort of a flowering plant from seeds (age 0) until all are dead. He marks the seedlings and comes back every year and counts how many living plants are remaining in the cohort. When they start to reproduce he counts the number of seeds per plant. Based on this information he writes the following incomplete life table:

| Age \(x\) | Remaining cohort \(n_x\) | Fecundity \(m_x\) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 12376 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 4233 | 0.0 |

| 2 | 1790 | 0.0 |

| 3 | 340 | 2.1 |

| 4 | 268 | 3.2 |

What is the age at first reproduction of this plant?

Create the same life table in R, with columns corresponding to Age \(x\), Remaining cohort \(n_x\), and fecundity \(m_x\).

Calculate the vectors of cumulative survival probability \(l_x\) and annual survival probability \(p_x\), and add these as columns to the life table you created.

Make plots of each life table column (\(n_x\), \(l_x\), \(p_x\), \(m_x\)) as a function of age \(x\). Describe the life history you see from the plot.

Calculate the mean lifetime reproduction \(R_0\) from the life table. What does this value say about the population growth rate?

Calculate the generation time \(T_C\) from the life table. What does this measure actually describe? What is the estimate of \(\lambda\) based on \(R_0\) and \(T_C\)?

Solve the Euler-Lotka equation for \(\lambda\) using the method demonstrated for the bird example. How does this value of \(\lambda\) differ from the estimate based on \(R_0\) and \(T_C\)?

Exercise 2.3

In the bird example (section 2.4.1), the values of fecundity given in table 2.1 correspond to the mean number of fledged female offspring per adult female. Assume that the offspring survival (from eggs to fledging) is 0.9, what is the average clutch size (number of eggs laid) at each age?

If we assume that the assumptions of the Lack clutch apply, what is the trade-off between offspring survival and offspring number at each age?

In another bird species, a close relative to this example bird, individuals only reproduce at age 3. Otherwise this species has the same average fitness and the same survivorship as in our bird example. What is the fecundity in this other species?

What is the name of the reproductive mode of the two bird species (the example bird and its relative)? Discuss why (or why not) the two species fit with the result of Cole’s paradox.